HABITAT DIORAMAS: Where art and nature meet

- MSU SciComm

- Jun 28, 2020

- 6 min read

Guest post by NICK VANACKER

MSU SciComm blog contest winner

Gorilla diorama at the American Museum of Natural History

Source: Wikimedia commons

Habitats across the world are being destroyed. Systematically, people are pushing further and further into wild places to feed a growing world – tearing down forests to build farms, draining wetlands to build cities, and stripping the world of its natural resources for profit. Species are being wiped out before they’re discovered. Animals are viewed as a near-limitless resource, and without government protection, they’re hunted endlessly – and those that aren’t are forced to face a rapidly changing world. Every day, we lose more biodiversity, and people don’t seem to care - mainly because they don’t know.

This is 1800’s America, and getting the word out isn’t simple. Photography and video are still in their infancy, so a new technology is invented to capture the beauty and dimension of what’s being systematically eradicated across the globe - the habitat diorama at the natural history museum.

Let’s jump forward to today. You enter a natural history museum - eager to see dinosaur skeletons, fossils of ancient life, rare gems and meteorites – and on your way, you pass hall after hall of taxidermied animals, preserved behind glass. Each animal lives inside a scene frozen in time; a gorilla in a misty rainforest, looking into the distance while beating his chest; a mother deer and two fawns, picking their way carefully through the Michigan woods; a group of giraffes, zebras, and rhinos gathered around a watering hole, keeping one eye out for the pack of painted lions in the distance.

These are habitat dioramas – museum displays that recreate biomes around the globe. Today, many visitors view dioramas as “dusty taxidermy behind glass” – but when they began, dioramas were revolutionary catalysts that inspired the modern conservation movement. They are also works of art that are falling into disrepair; and they continue to inform us about humanity’s impacts on our environment.

Animals have been on display in museums for a long time. A museum visitor in the 1800s would see skeletons and taxidermy mounts pressed together like sardines inside bare glass display cases. Labels and other text were rare, so unless they were being guided around by a museum curator, a visitor was left on their own to devices to figure out what they were staring at, and why it was important enough to be on display. The idea of presenting animals in an educational way, to tell stories like evolution, diversity, or extinction simply didn’t exist yet - until a man named Carl Akeley mounted a group of muskrats.

It was 1886, and Carl Akeley was a taxidermist at the Milwaukee Public Museum, where he focused on mounting animals native to Wisconsin – including muskrats. His methods not only created incredibly life-like dead animals such as muskrats, but also a life-like wetland to display them. Victorian taxidermists had placed taxidermied animals in recreated habitats before - Akeley’s innovation was his meticulous detail that made the habitats so vivid and lifelike that they seem to tell a story. Without any knowledge of muskrat biology, without even a label or curator to explain it, you can tell that these animals live in groups. They’re semi-aquatic, comfortable both swimming in water and walking on land. Through a cut-away, you can see one muskrat inside a lodge made of reeds and sticks – clearly, this group of animals made the structure themselves, and use it as their home. It’s no wonder that this new method of story-telling started to take the museum world by storm.

Akeley’s Muskrat Diorama at the Milwaukee Public Museum

Source: Wikimedia commons

Of course, if you’ve ever seen a nature documentary, you know the problem with telling stories about the lives of animals – they aren’t all tales of happy families of muskrats living in a marsh. Even in the 1800s, humans were challenging nature. America's huge herds of bison were destroyed systematically, as a way to weaken Native American groups. Settlers riding trains on their way out west developed a new game, which involved shooting as many bison as you could from the front of a moving train and leaving their bodies behind. Even museum people like William Temple Hornaday, a taxidermist at the Smithsonian, took part. In order to get the specimens to create a new habitat diorama calling attention to the imminent extinction of bison, he had to hunt down and kill some of the last remaining wild bison in the United States.

Pile of American bison skulls in Detroit (MI) waiting to be ground for fertilizer or charcoal

Source: Wikimedia commons (1892) An even bigger culprit was 19th century fashion, specifically the vogue for big women’s hats with big feathers. In a sort of arms race, women and their milliners seemed to compete to wear the most extravagant hat possible, which involved feathers from birds across the world. Sometimes, just the feathers weren’t enough, and a hat featured an entire taxidermied bird – which was usually hunted, sold, and mounted specifically to end up on someone’s head. Wading birds like herons, ibises and spoonbills were hunted in the millions, harvested during mating season when their feathers were at their finest, which resulted in fewer baby birds. People thought bird populations were indestructible – until ornithologists noticed they weren’t. The hat craze threatened as many of 67 types of bird with extinction. Others like the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet had gone extinct already, caught in the crossfire.

In 1900, Congress had passed the Lacey Act, which banned selling illegally harvested animal parts across state lines – but it wasn’t enough. Most of the birds in danger lived far off the beaten path, in hard to access swamps and wetlands. It was hard to convince politicians and the general public to enforce or support poaching bans to protect species they had never seen. The answer ended up being simple: bring the wetland to them.

Frank Chapman, an ornithologist, and his team at the American Museum of Natural History, created the Wading Birds Diorama, which recreated the Cuthbert Rookery in Florida– an almost inaccessible nesting site for thousands of endangered birds regularly harvested by “plume hunters” for the hat market. Even before the diorama’s official opening, Chapman invited President Theodore Roosevelt to see the diorama in person. He was so moved that it inspired him to create the nation’s first federal bird reservation at Pelican Island, another important refuge for Florida birds. This was the forerunner to our current National Wildlife Refuge System, and influenced the later founding of our national parks system.

Wading birds diorama at the American Museum of Natural History

Source: Wikimedia commons

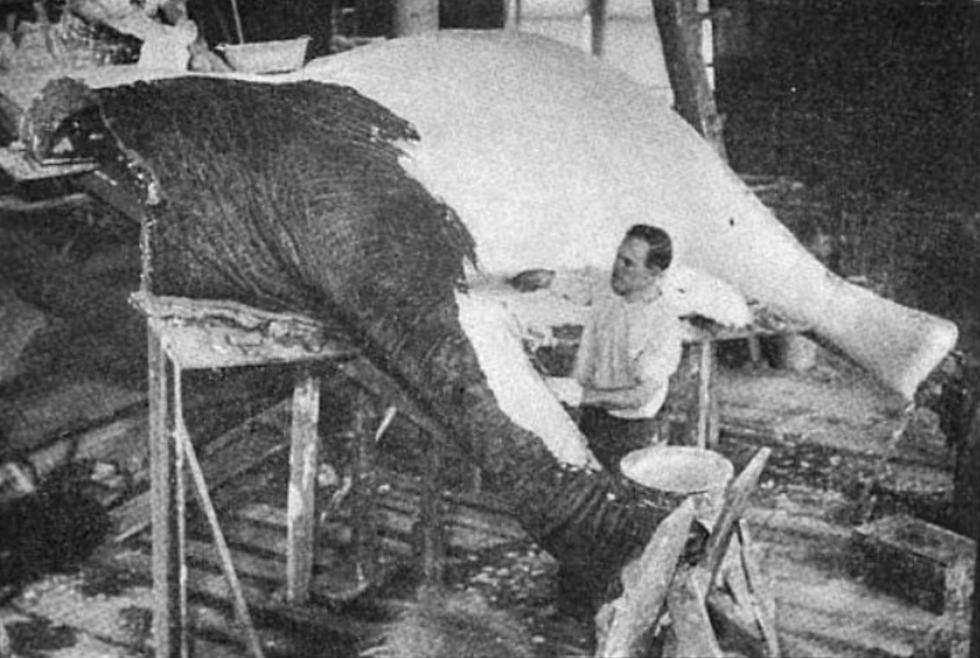

It may seem odd to think that a museum exhibit could move a president to enact an executive order, but a diorama is more than just an exhibit – each one is a work of art. For each diorama, a whole team of museum workers – scientists, artists, craftsmen and laborers spends countless hours sketching, sculpting, painting and constructing to recreate nature inside a small glass box. Habitat dioramas are created to evoke a specific place and moment in time – a valley in Africa during the rainy season, for instance. On expedition, scientists and artists collaborate, taking samples of everything from the particular location – the animal and plant life, the color of the dirt, making detailed illustrations and paintings, so the spot can be recreated in exact detail at the museum. Back home, countless pieces are sculpted and molded, painted and detailed. An artist may spend a month painting the detailed scenery in the background. Hundreds of leaves are cast in wax and placed by hand along a branch. Pieces of taxidermy were sculpted, mounted, painted, and placed with care.

Of course, the problem with preserving nature is that nature constantly changes. The Cuthbert Rookery is still inaccessible, but human changes to Florida’s waterways mean there are no longer giant flocks of wading birds. The bison habitat created by Hornaday is no longer accurate – once wide open, today bisected by roads and fences. The muskrat diorama falls short, too – there are very few wetlands in the world without some amount of pollution or human impact. It’s easy to say that habitat dioramas reflect nature in the past instead of nature in the present, but that’s not true - even when they were first created, habitat dioramas have never shown us what nature actually looks like. They show us a dream, a human idea of what nature could be – that maybe, somewhere out there, there are wide-open wild spaces with wildlife galore. Habitat dioramas have always airbrushed and spot-cleaned nature, to create a perfect, impossible environment – but one that we can’t help but fall in love with and try to protect. In this way, habitat dioramas are more than taxidermy behind glass. So long as they continue to inspire and educate future generations to protect, conserve and enjoy wild places, they’re doing what they’re meant to.

NICK VANACKER is an alumnus of the College of Natural Science at MSU and currently works as an educator at the Michigan State University Museum, creating programs, events, exhibits, and activities related to biology, paleontology, and evolution. When not in museums, Nick considers himself an amateur naturalist, and can be found birding, herping, sketching mushrooms, pressing plants, pinning insects, or doing taxidermy.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES:

Akeley at work: Wikimedia commons

Women's hat, Edwardian era: Wikimedia commons

I would strongly recommend you points viewers to Donna Haraway's Primate Visions. She pioneered the arguments you are making and is a good friend of animal studies at MSU (animalstudies.msu.edu)